Black Cowboys: Reclaiming Their History and Their Present

Celebrating Black History Month

The chinking sound of spurs against the sidewalk, the dull rustle of leather chaps, the musky smell of being on the trail for too many weeks and the bowlegged swagger of a cowboy walking into a dark saloon to wash the dust out of his mouth. This timeless image of the trailblazing, sharpshooting, horseback-riding cowboy has defined the spirit of Texas. The cowboy is a uniquely American invention and, like most American inventions, has its roots in the blending of different cultures and traditions.

The origin of the cowboy began with the arrival of the Spanish explorers. On the ships going to the New World were some of the first cowboys, Africans slaves tasked with herding cattle the Spanish brought. The Spanish vaqueros taught them how to ride horses and rope and herd cattle. Later, in the early 1800s, slaveowners from southeastern states such as Alabama and Tennessee moved into Texas in search of cheap land. Among the slaves they brought were skilled horsemen adept at roping and branding cattle. In 1861, Texas joined the Confederacy, and while battles fought on Texas soil were rare, many Texans took up arms to fight the war outside of Texas. The Confederate ranchers depended on their slaves to maintain their land and cattle herds in their absence. In doing so, the slaves further honed the skills needed to tend cattle, talents that served them well when the war came to an end.

The chaotic time of the Civil War found many ranchers returning home only to discover their herds were lost or scattered. They needed help to round up these maverick cattle, but the Emancipation Proclamation left them without the slaves on which they were so dependent. Ranchers were now obliged to hire the newly freed slaves as paid cowhands. Being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to the freedmen who chose to remain in rural areas rather than migrate to cities.

They found themselves in even greater demand when ranchers began selling their livestock in northern states where, due to food shortages brought on by the war, beef had become a valuable commodity. Since Texas lacked sufficient railroad lines, enormous herds of cattle had to be driven across the open plains to shipping centers in Kansas, Colorado and Missouri. Rounding up the herds on horseback, cowboys of all colors traversed northward up trails fraught with danger, harsh weather and the occasional Indian attack.

One in four cowboys going up the trail were Black. The journey was long and isolating. Cowboys had to depend upon each other to share a blanket, a plate of beans, or a song at the end of a long day. During a stampede or a storm, it didn’t matter which of your trail mates was white, brown or black. You relied upon them all for your survival. While Black cowboys faced discrimination in the towns they passed through, they found camaraderie and respect with the other trail drivers who valued them for their skill, loyalty and work ethic. The Black cowboy enjoyed a level of equality many other Blacks did not during the years after the Civil War.

With the invention of barb wire that fenced off the open plains, cattle drives came to an end by the late 1800s. Many cowboys had to seek jobs in other fields while some Black cowboys returned to work on ranches owned by white property owners since owning property themselves could be difficult during the Jim Crow era. Though opportunities for working cowboys were on the decline, the public’s fascination with the cowboy lifestyle was only beginning, leading to the popularity of Wild West shows and rodeos.

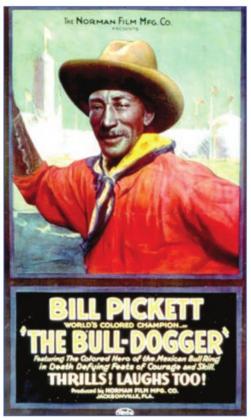

For a lucky few, the Wild West shows and rodeos gave them another chance of continuing to live the cowboy way of life. Bill Pickett, the oldest of 13 children born in Williamson County to former slaves, invented the practice of bulldogging. It consisted of jumping on a steer from a horse and wrestling the steer to the ground by biting the steer’s lip. Pickett said he got the idea watching dogs do the same thing when they were herding cows. Pickett demonstrated his unique skills all over the world with the Miller Brothers’ 101 Wild Ranch Show. Cowboy actor Tom Mix and humorist Will Rogers were among the people who served as Pickett’s assistant. In 1972, 40 years after his death, Pickett became the first black honoree in the National Rodeo Hall of Fame, and a version of bulldogging, or steer wrestling, is still a rodeo event today.

Pickett was just the beginning of a long tradition of Black rodeo cowboys. Cleo Hearn has been a professional cowboy since 1959. In his early days, he faced discrimination on where he could compete and train. It was Ray Wharton who invited Hearn to come to Bandera to train with him In an article for the Smithsonian Magazine, he recalled being barred from entering a rodeo in his hometown of Seminole, Oklahoma, when he was 16 years old because the rodeo producers would not let Black cowboys rope in front of the crowd. They had to rope in the evenings or in the mornings before the audience came.

In 1971, Hearn established the Cowboys of Color Rodeo. The touring rodeo features athletes of different ethnicities who compete at several different rodeos throughout the year, including the wellknown Fort Worth Stock Show and Rodeo. Hearn not only trains young cowboys and cowgirls to enter the professional rodeo industry; his rodeo’s goals are two-fold. “The theme of Cowboys of Color is let us educate you while we entertain you,” he explained in the Smithsonian Magazine. “Let us tell you the wonderful things Blacks, Hispanics and Indians did for the settling of the West that history books have left out.”

Both Cleo Hearn and Bill Pickett are inductees in the Frontier Times Museum’s Texas Heroes Hall of Honor. Cowboy traditions are richer with the many contributions Black cowboys have made to our western heritage.

Rebecca Norton is the Executive Director of the Frontier Time Museum